Rivers of Bangladesh

Brahmaputra River

The Brahmaputra (/ˌbrɑːməˈpuːtrə/ is

one of the major rivers of Asia, a trans-boundary river which flows

through China, India and Bangladesh. As such, it is known by various names in

the region: Assamese: ব্ৰহ্মপুত্ৰ নদ ('নদ' nôd,

masculine form of 'নদী' nôdi "river") Brôhmôputrô [bɹɔɦmɔputɹɔ]; Sanskrit: ब्रह्मपुत्र, IAST: Brahmaputra; Tibetan: ཡར་ཀླུངས་གཙང་པོ་, Wylie: yar klung

gtsang po Yarlung Tsangpo; simplified Chinese: 布拉马普特拉河; traditional Chinese: 布拉馬普特拉河; pinyin: Bùlāmǎpǔtèlā

Hé. It is also called Tsangpo-Brahmaputra (when referring to the whole

river including the stretch within Tibet). The Manas River, which

runs through Bhutan, joins it at Jogighopa, in India. It is the

tenth largest river in the world by discharge, and the 15th longest.

With its origin in the Angsi glacier, located on the

northern side of the Himalayas in Burang County of Tibet as

the Yarlung Tsangpo River,it flows across southern Tibet to

break through the Himalayas in great gorges (including the Yarlung Tsangpo

Grand Canyon) and into Arunachal Pradesh (India).It flows southwest

through the Assam Valley as Brahmaputra and south through Bangladesh as

the Jamuna (not to be mistaken with Yamuna of India). In

the vast Ganges Delta, it merges with the Padma, the popular name of

the river Ganges in Bangladesh, and finally the Meghna and

from here it is known as Meghna before emptying into the Bay of Bengal.

About 3,848 km (2,391 mi) long, the

Brahmaputra is an important river for irrigation and transportation.

The average depth of the river is 38 m (124 ft) and maximum depth is

120 m (380 ft). The river is prone to catastrophic flooding in the

spring when Himalayas snow melts. The average discharge of the river is about

19,800 m3/s (700,000 cu ft/s),and

floods can reach over 100,000 m3/s

(3,500,000 cu ft/s). It is a classic example of a braided

river and is highly susceptible to channel migration and avulsion.It

is also one of the few rivers in the world that exhibit a tidal bore. It

is navigable for most of its length.

The river drains the Himalaya east of the Indo-Nepal border,

south-central portion of the Tibetan plateau above the Gangabasin,

south-eastern portion of Tibet, the Patkai-Bum hills, the northern slopes

of the Meghalaya hills, the Assam plains, and the northern portion of

Bangladesh. The basin, especially south of Tibet, is characterized by high

levels of rainfall. Kangchenjunga (8,586 m) is the only peak above

8,000 m, hence is the highest point within the Brahmaputra basin.

The Brahmaputra's upper course was long unknown, and its

identity with the Yarlung Tsangpo was only established by exploration in

1884–86. This river is often called Tsangpo-Brahmaputra river.

Padma River

The Padma (Bengali: পদ্মা Pôdda) is a major river in Bangladesh. It is the main distributary of the Ganges,

flowing generally southeast for 120 kilometres (75 mi) to its confluence

with the Meghna River near the Bay of Bengal.The city of Rajshahi is

situated on the banks of the river.

History

Etymology

The Padma, Sanskrit for lotus

flower, is mentioned

in Hindu mythology as a byname for the Goddess Lakshmi.

The name Padma is given to the lower part of

the course of the Ganges (Ganga) below the point of the off-take of the Bhagirathi

River(India), another

Ganges River distributary also known as the Hooghly

River. Padma had, most

probably, flowed through a number of channels at different times. Some authors

contend that each distributary of the Ganges in its deltaic part is a remnant

of an old principal channel, and that starting from the western-most one, the

Bhagirathi (in West Bengal, India), each distributary to the east marks a

position of a newer channel than the one to the west of it.

Geographic effects

Padma River and boats (1860)

Eighteenth-century geographer James

Rennell referred to a

former course of the Ganges north of its present channel, as follows:

Appearances favour very strongly that the Ganges had its former

bed in the tract now occupied by the lakes and morasses between Natore and

Jaffiergunge, striking out of the present course by Bauleah to a junction of

Burrrampooter or Megna near Fringybazar, where accumulation of two such mighty

streams probably scooped out the present amazing bed of the Megna.

The places mentioned by Rennell proceeding from west to east

are Rampur Boali, the headquarters

of Rajshahi district, Puthia and Natore in

the same district and Jaffarganj in the district of Dhaka. The place last named were shown in a map of

the Mymensinghdistrict

dated 1861, as a subdistrict (thana) headquarters, about 10 kilometres

(6 mi) south-east of Bera Upazila police

station. It is now known as Payla Jaffarganj and is close to Elachipur

opposite Goalunda. According to Rennell's theory,

therefore, the probable former course of the Ganges would correspond with that

of the present channel of the Baral River.

Authorities agree that the Ganges has changed its course and

that at different times, each of the distributaries might have been the carrier

of its main stream.

The bed of the Padma is wide, and the river is split up into

several channels flowing between constantly shifting sand banks and islands.

During the rains the current is very strong and even steamers may find

difficulty in making headway against it. It is navigable at all seasons of the

year by steamers and country boats of all sizes and until recently ranked as

one of the most frequented waterways in the world. It is spanned near Paksey by

the great Hardinge Bridge over which runs one of the

main lines of the Bangladesh Railway.

Hardinge Bridge in Bangladesh

Geography

The Padma enters Bangladesh from India near Nawabganj and meets the Jamuna (Bengali: যমুনা Jomuna)

near Aricha and retains its name, but finally meets with the Meghna (Bengali: মেঘনা) near Chandpur and

adopts the name "Meghna" before flowing into the Bay

of Bengal.

Rajshahi, a major city in western Bangladesh, is

situated on the north bank of the Padma.

The Ganges originates in the Gangotri Glacier

of the Himalaya, and runs through India and Bangladesh to the Bay of Bengal.

The Ganges enters Bangladesh at Shibganj in the district of Chapai Nababganj.

West of Shibganj, the Ganges branches into two distributaries, the Bhagirathi and the Padma rivers. The Bhagirathi

River, which flows southwards, is also known as the Ganga and was named the

Hoogly or Hooghly River by the British.

Further downstream, in Goalando, 2,200 kilometres

(1,400 mi) from the source, the Padma is joined by the Jamuna (Lower Brahmaputra) and the resulting combination flows with the

name Padma further east, to Chandpur. Here, the widest river in Bangladesh, the

Meghna joins the Padma, continuing as the Meghna almost in a straight line to

the south, ending in the Bay of Bengal.

Sunset from Padma River

Pabna District

A view of Padma river in summer near Rajshahi

The Padma forms the whole of the southern boundary of the Pabna District for

a distance of about 120 kilometres (75 mi).

Kushtia District

The Jalangi River is thrown off at the point

where the mighty Padma touches the district at its most northernly corner, and

flows along the northern border in a direction slightly southeast, until it

leaves the district some miles to the east of Kushtia. It carries immense volumes of water and is

very wide at places, constantly shifting its main channel, eroding vast areas

on one bank, throwing chars on the other, giving rise to many disputes as to

the possession of the chars and islands which are thrown up.

Rajshahi District

Rajshahi is the largest city among the cities which is situated

on the bank of Padma river. It is the third largest city in Bangladesh. It is a

major city in the north Bengal. Rajshahi has a beautifully decorated embankment

of Padma. Rajshahi Collegiate School is one of the oldest schools in Indian

Subcontinent, situated on Padma river bank. The school was endangered three

times by the disintegration of the Padma river. Padma Food Garden, A.H.M.

Kamaruzzaman Central Park and Zoo, Barokuthi Nandan Park, Muktamancha, and 'T'

shaped embankment (Bengali: টি বাঁধ) are best tourist spot in Rajshahi which are

situared on the bank of Padma river.

Sunset from the river Padma during monsoon,

Rajpara, Rajshahi

Infrastructure

Sky over river padma

Damming

After the construction of the Farakka Barrage on

the Ganges River in West

Bengal, the maximum flows in

the Padma River were reduced significantly. The flow reduction caused many

problems in Bangladesh, including the loss of fish species, the drying of

Padma's distributaries, increased saltwater intrusion from the Bay of Bengal,

and damage to the mangrove forests of the Sundarbans.

Padma Bridge

The Padma

Bridge would be

Bangladesh's largest, estimated at US$2.3 billion to finish. It was supposed to

be open to the public in 2013. However, the future of the project became

uncertain when in June 2012 the World

Bank cancelled its

$1.2 billion loan over corruption allegations. In June 2014, the government of

Bangladesh, proceeding without the loan, hired a Chinese firm to construct the

6.15-kilometre (3.82 mi) main part of the bridge, and in October 2014, it

hired a South Korean firm to supervise construction. Officials aim to finish

the project by 2018.In 2009, government plans also included

rail lines on both sides of the Padma with a connection via the new bridge.

Lalon Shah Bridge, also

known as the Paksey Bridge, is a road bridge in Bangladesh over the river

Padma, situated between Ishwardi Upazila of Pabna on the east, and Bheramara

Upazila of Kushtia on the west.

Ganges

The Ganges (/ˈɡændʒiːz/ GAN-jeez), also known

as Ganga (Hindustani: [ˈɡəŋɡaː]), is a trans-boundary river of Asia which

flows through the nations of India and Bangladesh. The

2,525 km (1,569 mi) river rises in the eastern Himalayas in

the Indian state of Uttarakhand, and flows south and east through

the Gangetic Plain of North

India. After entering West Bengal, it is divided into two rivers, one

is Hugly river or Adi Ganga, flowing through several districts of West Bengal

and finally submerged with Bay of Bengal near Ganga

Sagar. The second part is named as Padma which

flows into Bangladesh, where it empties into the Bay of

Bengal. It is the third largest river in the world by discharge.

The Ganges is one of the most sacred rivers to Hindus,

although it is not mentioned in either the Rigveda or

the Ramayana.It is also a lifeline to millions of Indians

who live along its course and depend on it for their daily needs. It is

worshipped as the goddess Ganga in Hinduism.It has also been important historically,

with many former provincial or imperial capitals (such as Kannauj, Kampilya, Kara, Prayag or Allahabad, Kashi, Pataliputra or Patna, Hajipur, Munger, Bhagalpur, Murshidabad, Baharampur, Nabadwip, Saptagram, Kolkata and Dhaka) located

on its banks.

The Ganges is highly polluted. Pollution threatens not only

humans, but also more than 140 fish species, 90 amphibian species and the

endangered Ganges river dolphin. The levels of fecal

coliform from human waste in the waters of the river near Varanasi are

more than 100 times the Indian government's official limit. The Ganga

Action Plan, an environmental initiative to clean up the river, has been a

major failure thus far, due to corruption, technical expertise, poor

environmental planning,and lack of support from religious authorities.

Geology

The Indian subcontinent lies atop the Indian

tectonic plate, a minor plate within the Indo-Australian Plate. Its defining geological

processes commenced seventy-five million years ago, when, as a part of the

southern supercontinent Gondwana, it began a

northeastwards drift—lasting

fifty million years—across the then unformed Indian Ocean. The

subcontinent's subsequent collision with the Eurasian

Plate and subductionunder it,

gave rise to the Himalayas, the planet's highest mountain

ranges. In the former seabed immediately south of the emerging Himalayas,

plate movement created a vast trough, which,

having gradually been filled with sediment borne by the Indus and

its tributaries and the Ganges and its tributaries, now forms the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

Hydrology

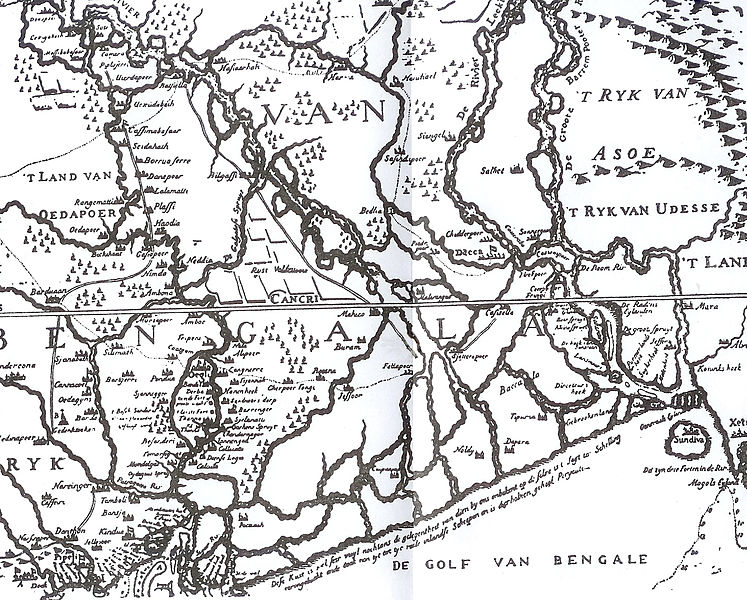

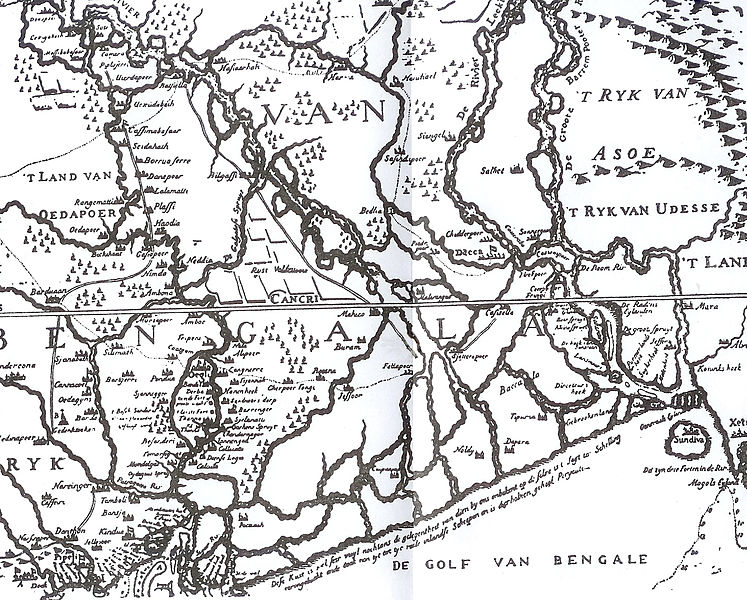

A 1908 map

showing the course of the Ganges and its tributaries.

Catchment

region of the Ganga

Major

left-bank tributaries include Gomti (Gumti), Ghaghara

(Gogra), Gandaki (Gandak),

and Kosi (Kusi); major right-bank tributaries

include Yamuna (Jumna), Son, Punpunand Damodar.

The hydrology of the Ganges River is very

complicated, especially in the Ganges Delta region. One result is different

ways to determine the river's length, its discharge, and the size of its drainage

basin.

Lower

Ganges in Lakshmipur, Bangladesh

The name Ganges is used for the river between

the confluence of the Bhagirathi and

Alaknanda rivers, in the Himalayas, and the India-Bangladesh border, near

the Farakka Barrage and

the first bifurcation of the river. The length of the Ganges

is frequently said to be slightly over 2,500 km (1,600 mi) long,

about 2,505 km (1,557 mi), to 2,525 km (1,569 mi), or

perhaps 2,550 km (1,580 mi). In these cases the river's source

is usually assumed to be the source of the Bhagirathi River, Gangotri Glacier at Gomukh, and its mouth being the mouth of the

Meghna River on the Bay of Bengal. Sometimes the source of the Ganges is

considered to be at Haridwar, where its

Himalayan headwater streams debouch onto the Gangetic Plain.

In some cases, the length of the Ganges is given for its Hooghly

River distributary, which is longer than its main outlet via the Meghna River,

resulting in a total length of about 2,620 km (1,630 mi), from the

source of the Bhagirathi,[or 2,135 km (1,327 mi),

from Haridwar to the Hooghly's mouth. In other cases the length is said to

be about 2,240 km (1,390 mi), from the source of the Bhagirathi to

the Bangladesh border, where its name changes to Padma.

For similar reasons, sources differ over the size of the river's

drainage basin. The basin covers parts of four countries, India, Nepal, China, and Bangladesh; eleven

Indian states, Himachal

Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar

Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Punjab,

Haryana, Rajasthan, West Bengal, and the Union Territory

of Delhi.The Ganges basin, including the delta

but not the Brahmaputra or Meghna basins, is about 1,080,000 km2 (420,000 sq mi),

of which 861,000 km2 (332,000 sq mi)

are in India (about 80%), 140,000 km2(54,000 sq mi)

in Nepal (13%), 46,000 km2 (18,000 sq mi)

in Bangladesh (4%), and 33,000 km2 (13,000 sq mi)

in China (3%).Sometimes the Ganges and Brahmaputra–Meghna drainage basins are

combined for a total of about 1,600,000 km2 (620,000 sq mi),or

1,621,000 km2(626,000 sq mi). The combined

Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin (abbreviated GBM or GMB) drainage

basin is spread across Bangladesh, Bhutan, India,

Nepal, and China.

The Ganges basin ranges from the Himalaya and

the Transhimalaya in

the north, to the northern slopes of the Vindhya range

in the south, from the eastern slopes of the Aravalli in

the west to the Chota Nagpur plateau and

the Sunderbans delta in the east. A

significant portion of the discharge from the Ganges comes from the Himalayan

mountain system. Within the Himalaya, the Ganges basin spreads almost

1,200 km from the Yamuna-Satluj divide along the Simla ridge forming the

boundary with the Indus basin in the west to the Singalila Ridge along the

Nepal-Sikkim border forming the boundary with the Brahmaputra basin

in the east. This section of the Himalaya contains 9 of the 14 highest peaks in

the world over 8,000m in height, including Mount

Everest which is the high point of the Ganges basin. The

other peaks over 8,000m in the basin are Kangchenjunga, Lhotse, Makalu, Cho Oyu, Dhaulagiri, Manaslu, Annapurna and Shishapangma. The Himalayan portion of

the basin includes the south-eastern portion of the state of Himachal Pradesh,

the entire state of Uttarakhand, the entire country of Nepal and the extreme

north-western portion of the state of West Bengal.

The discharge of the Ganges also differs by source. Frequently,

discharge is described for the mouth of the Meghna River, thus combining the

Ganges with the Brahmaputra and Meghna. This results in a total average

annual discharge of about 38,000 m3/s

(1,300,000 cu ft/s), or 42,470 m3/s

(1,500,000 cu ft/s). In other cases the average annual

discharges of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna are given separately, at

about 16,650 m3/s (588,000 cu ft/s) for the Ganges, about

19,820 m3/s (700,000 cu ft/s) for the Brahmaputra, and about

5,100 m3/s (180,000 cu ft/s) for the Meghna.

Hardinge

Bridge, Bangladesh, crosses the Ganges-Padma River. It is one of the

key sites for measuring streamflow and discharge on the lower Ganges.

The maximum peak discharge of the Ganges, as recorded at Hardinge Bridge in Bangladesh, exceeded

70,000 m3/s (2,500,000 cu ft/s).The minimum recorded at the

same place was about 180 m3/s

(6,400 cu ft/s), in 1997.

The hydrologic cycle in the Ganges basin is governed by

the Southwest Monsoon. About

84% of the total rainfall occurs in the monsoon from June to September.

Consequently, streamflow in the Ganges is highly seasonal. The

average dry season to monsoon discharge ratio is about 1:6, as measured

at Hardinge Bridge.

This strong seasonal variation underlies many problems of land and water

resource development in the region.The seasonality of flow is so acute it can

cause both drought and floods. Bangladesh, in particular, frequently experiences drought during

the dry season and regularly suffers extreme floods during the monsoon.

In the Ganges Delta many large rivers come together, both

merging and bifurcating in

a complicated network of channels. The two largest rivers, the Ganges

and Brahmaputra, both split into distributary channels, the

largest of which merge with other large rivers before themselves joining. This

current channel pattern was not always the case. Over time the rivers in Ganges

Delta have changed course, sometimes altering the network

of channels in significant ways.

Before the late 12th century the Bhagirathi-Hooghly distributary

was the main channel of the Ganges and the Padma was only a minor

spill-channel. The main flow of the river reached the sea not via the modern

Hooghly River but rather by the Adi Ganga. Between the 12th and 16th centuries

the Bhagirathi-Hooghly and Padma channels were more or less equally

significant. After the 16th century the Padma grew to become the main channel

of the Ganges.It is thought that the Bhagirathi-Hooghly became increasingly

choked with silt, causing the main flow of the Ganges to shift to the southeast

and the Padma River. By the end of the 18th century the Padma had become the

main distributary of the Ganges. One result of this shift to the Padma was

that the Ganges joined the Meghna and Brahmaputra rivers before emptying into

the Bay of Bengal, together instead of separately. The present confluence of

the Ganges and Meghna formed about 150 years ago.

Also near the end of the 18th century, the course of the lower

Brahmaputra changed dramatically, altering its relationship with the Ganges. In

1787 there was a great flood on the Teesta River, which at the time was a

tributary of the Ganges-Padma River. The flood of 1787 caused the Teesta to

undergo a sudden change course (an avulsion),

shifting east to join the Brahmaputra and causing the Brahmaputra to shift its

course south, cutting a new channel. This new main channel of the Brahmaputra

is called the Jamuna River. It flows south to join the Ganges-Padma. Since

ancient times the main flow of the Brahmaputra was more easterly, passing by

the city of Mymensingh and

joining the Meghna River. Today this channel is a small distributary but

retains the name Brahmaputra, sometimes Old Brahmaputra.The site of the old

Brahmaputra-Meghna confluence, in the locality of Langalbandh, is still considered sacred by

Hindus. Near the confluence is a major early historic site called Wari-Bateshwar.

History

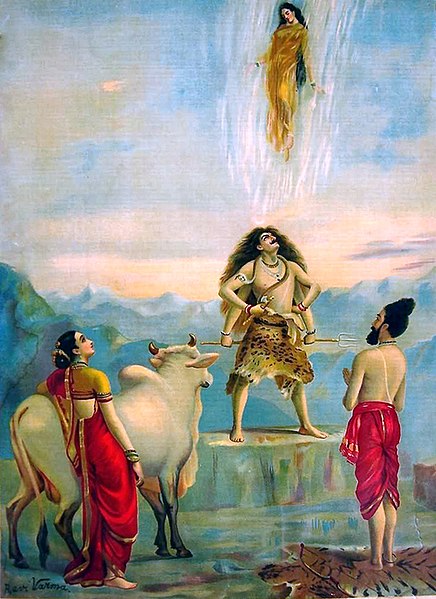

The birth

of Ganges

The Late Harappan period,

about 1900–1300 BCE, saw the spread of Harappan settlement eastward from

the Indus River basin to the Ganges-Yamuna doab,

although none crossed the Ganges to settle its eastern bank. The disintegration

of the Harappan civilisation, in the early 2nd

millennium BC, marks the point when the centre of Indian civilisation shifted

from the Indus basin to the Ganges basin. There may be links between the

Late Harappan settlement of the Ganges basin and the archaeological culture known as "Cemetery H", the Indo-Aryan

people, and the Vedic

period.

This river is the longest in India.During the early Vedic Age of

the Rigveda, the

Indus and the Sarasvati

River were the major sacred rivers, not the Ganges. But the

later three Vedas gave much more importance to the Ganges. The Gangetic

Plain became the centre of successive powerful states, from the Maurya Empire to the Mughal

Empire.

The first European traveller to mention the Ganges was Megasthenes (ca. 350–290 BCE). He did so

several times in his work Indica:

"India, again, possesses many rivers both large and navigable, which,

having their sources in the mountains which stretch along the northern

frontier, traverse the level country, and not a few of these, after uniting

with each other, fall into the river called the Ganges. Now this river, which

at its source is 30 stadia broad, flows from north to south, and empties

its waters into the ocean forming the eastern boundary of the Gangaridai, a nation which possesses a vast

force of the largest-sized elephants." (Diodorus II.37) In the rainy

season of 1809, the lower channel of the Bhagirathi, leading to Kolkata, had been

entirely shut; but in the following year it opened again, and was nearly of the

same size with the upper channel; both however suffered a considerable

diminution, owing probably to the new communication opened below the Jalanggi

on the upper channel.

In 1951 a water sharing dispute arose

between India and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), after

India declared its intention to build the Farakka Barrage. The original purpose of the

barrage, which was completed in 1975, was to divert up to 1,100 m3/s

(39,000 cu ft/s) of water from the Ganges to the Bhagirathi-Hooghly

distributary in order to restore navigability at the Port of

Kolkata. It was assumed that during the worst dry season the Ganges

flow would be around 1,400 to 1,600 m3/s

(49,000 to 57,000 cu ft/s), thus leaving 280 to 420 m3/s (9,900

to 14,800 cu ft/s) for the then East Pakistan. East Pakistan

objected and a protracted dispute ensued. In 1996 a 30-year treaty was signed

with Bangladesh. The terms of the agreement are complicated, but in essence

they state that if the Ganges flow at Farakka was less than 2,000 m3/s

(71,000 cu ft/s) then India and Bangladesh would each receive 50% of

the water, with each receiving at least 1,000 m3/s

(35,000 cu ft/s) for alternating ten-day periods. However, within a

year the flow at Farakka fell to levels far below the historic average, making

it impossible to implement the guaranteed sharing of water. In March 1997, flow

of the Ganges in Bangladesh dropped to its lowest ever, 180 m3/s

(6,400 cu ft/s). Dry season flows returned to normal levels in the

years following, but efforts were made to address the problem. One plan is for

another barrage to be built in Bangladesh at Pangsha, west of Dhaka. This

barrage would help Bangladesh better utilise its share of the waters of the

Ganges.

Religious and cultural

significance

Embodiment

of sacredness

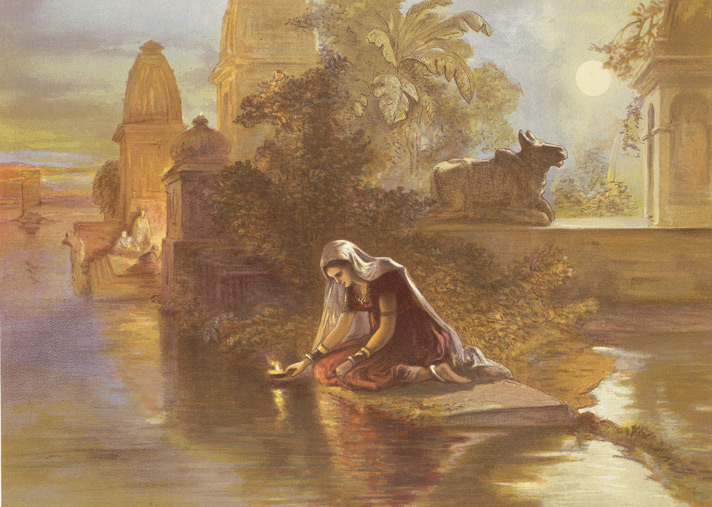

Chromolithograph,

"Indian woman floating lamps on the Ganges," by William Simpson,

1867.

The Ganges is a sacred river to Hindus along every fragment of

its length. All along its course, Hindus bathe in its waters, paying

homage to their ancestors and to their gods by cupping the water in their

hands, lifting it and letting it fall back into the river; they offer flowers

and rose petals and float shallow clay dishes filled with oil and lit with

wicks (diyas). On the journey back home from the Ganges, they carry small

quantities of river water with them for use in rituals (Ganga jal, literally

water of the Ganges).

The Ganges is the embodiment of all sacred waters in Hindu

mythology. Local rivers are said to be like the

Ganges, and are sometimes called the local Ganges (Ganga). The Kaveri river of Karnataka and Tamil

Nadu in Southern India is called the Ganges of the South;

the Godavari, is the Ganges that was led by the

sage Gautama to flow through Central India.

The Ganges is invoked whenever water is used in Hindu ritual, and is

therefore present in all sacred waters. In spite of this, nothing is more

stirring for a Hindu than a dip in the actual river, which is thought to remit

sins, especially at one of the famous tirthas such

as Gangotri, Haridwar, Prayag, or Varanasi. The

symbolic and religious importance of the Ganges is one of the few things that

Hindu India, even its skeptics, are agreed upon. Jawaharlal Nehru, a

religious iconoclast himself, asked for a handful of his ashes to be thrown

into the Ganges. "The Ganga," he wrote in his will, "is the

river of India, beloved of her people, round which are intertwined her racial

memories, her hopes and fears, her songs of triumph, her victories and her

defeats. She has been a symbol of India's age-long culture and civilization,

ever-changing, ever-flowing, and yet ever the same Ganga.

Avatarana or Descent of the Ganges

In late May or early June every year, Hindus celebrate the avatarana or

descent of the Ganges from heaven to earth. The day of the

celebration, Ganga Dashahara, the dashami (tenth

day) of the waxing moon of the Hindu

calendar month Jyestha, brings throngs of

bathers to the banks of the river.A soak in the Ganges on this day is said to

rid the bather of ten sins (dasha = Sanskrit "ten"; hara = to

destroy) or alternatively, ten lifetimes of sins. Those who cannot journey

to the river, however, can achieve the same results by bathing in any nearby

body of water, which, for the true believer, in the Hindu tradition, takes on

all the attributes of the Ganges.

The avatarana is an old theme in Hinduism with

a number of different versions of the story.In the Vedic version, Indra,

the Lord of Svarga(Heaven) slays

the celestial serpent, Vritra,

releasing the celestial liquid, the soma, or the

nectar of the gods which then plunges to the earth and waters it with

sustenance.

In the Vaishnava version

of the myth, Indra has been replaced by his former helper Vishnu. The

heavenly waters are now a river called Vishnupadi (padi:

Skt. "from the foot of").As he completes his celebrated three

strides—of earth, sky, and heaven—Vishnu as Vamana stubs his toe on the vault of

heaven, punches open a hole, and releases the Vishnupadi, which

until now had been circling around the cosmic egg within. Flowing out of

the vault, she plummets down to Indra's heaven, where she is received by Dhruva, the

once steadfast worshipper of Vishnu, now fixed in the sky as the polestar. Next,

she streams across the sky forming the Milky Way and

arrives on the moon. She then flows down earthwards to Brahma's realm,

a divine lotus atop Mount

Meru, whose petals form the earthly continents. There, the divine

waters break up, with one stream, the Alaknanda, flowing down one petal into

Bharatvarsha (India) as the Ganges.

It is Shiva, however, among the major deities of the Hindu pantheon, who

appears in the most widely known version of the avatarana story. Told

and retold in the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and

several Puranas, the story begins with a sage, Kapila, whose intense meditation has been

disturbed by the sixty thousand sons of King Sagara.

Livid at being disturbed, Kapila sears them with his angry gaze, reduces them

to ashes, and dispatches them to the netherworld. Only the waters of the

Ganges, then in heaven, can bring the dead sons their salvation. A descendant

of these sons, King Bhagiratha, anxious to

restore his ancestors, undertakes rigorous penance and is eventually granted

the prize of Ganga's descent from heaven. However, since her turbulent force

would also shatter the earth, Bhagiratha persuades Shiva in his abode on Mount

Kailash to receive Ganga in the coils of his tangled hair and

break her fall. Ganga descends, is tamed in Shiva's locks, and arrives in the

Himalayas. She is then led by the waiting Bhagiratha down into the plains at

Haridwar, across the plains first to the confluence with the Yamuna at

Prayag and then to Varanasi, and eventually to Ganga

Sagar, where she meets the ocean, sinks to the netherworld, and saves

the sons of Sagara.In honour of Bhagirath's pivotal role in the avatarana,

the source stream of the Ganges in the Himalayas is named Bhagirathi,

(Sanskrit, "of Bhagiratha").

Redemption

of the Dead

Preparations

for cremations on the banks of the Ganges in Varanasi, 1903.

The dead are being bathed, wrapped in cloth and covered with wood. The

photograph has caption, "Who dies in the waters of the Ganges obtains

heaven."

Since Ganga had descended from heaven to earth, she is also the

vehicle of ascent, from earth to heaven. As the Triloka-patha-gamini,

(Skt. triloka= "three worlds", patha =

"road", gamini = "one who travels") of the

Hindu tradition, she flows in heaven, earth, and

the netherworld, and,

consequently, is a "tirtha," or crossing point of all beings, the

living as well as the dead. It is for this reason that the story of

the avatarana is told at Shraddha ceremonies

for the deceased in Hinduism, and Ganges water is used in Vedic rituals after death.Among

all hymns devoted to the Ganges, there are none more popular than the ones

expressing the worshipers wish to breathe his last surrounded by her

waters.The Gangashtakam expresses this longing fervently:

O Mother! ... Necklace adorning the worlds!

Banner rising to heaven!

I ask that I may leave of this body on your banks,

Drinking your water, rolling in your waves,

Remembering your name, bestowing my gaze upon you.

Banner rising to heaven!

I ask that I may leave of this body on your banks,

Drinking your water, rolling in your waves,

Remembering your name, bestowing my gaze upon you.

No place along her banks is more longed for at the moment of

death by Hindus than Varanasi, the Great Cremation Ground, or Mahashmshana Those who are lucky

enough to die in Varanasi, are cremated on the banks of the Ganges, and are

granted instant salvation.If the death has occurred elsewhere, salvation can be

achieved by immersing the ashes in the Ganges. If the ashes have been

immersed in another body of water, a relative can still gain salvation for the

deceased by journeying to the Ganges, if possible during the lunar

"fortnight of the ancestors" in the Hindu calendar month of Ashwin (September or October), and

performing the Shraddha rites.

Hindus also perform pinda pradana, a rite for the dead,

in which balls of rice and sesame seed are offered to the Ganges while the

names of the deceased relatives are recited. Every sesame seed in every

ball thus offered, according to one story, assures a thousand years of heavenly

salvation for the each relative.Indeed, the Ganges is so important in the

rituals after death that the Mahabharata, in one of its

popular ślokas, says, "If only (one) bone of a (deceased)

person should touch the water of the Ganges, that person shall dwell honoured

in heaven. As if to illustrate this truism, the Kashi Khanda (Varanasi

Chapter) of the Skanda Purana recounts

the remarkable story of Vahika, a profligate and unrepentant sinner,

who is killed by a tiger in the forest. His soul arrives before Yama, the

Lord of Death, to be judged for the hereafter. Having no compensating virtue,

Vahika's soul is at once dispatched to hell. While

this is happening, his body on earth, however, is being picked at by vultures,

one of whom flies away with a foot bone. Another bird comes after the vulture,

and in fighting him off, the vulture accidentally drops the bone into the

Ganges below. Blessed by this happenstance, Vahika, on his way to hell, is

rescued by a celestial chariot which takes him instead to heaven.

The

Purifying Ganges

Devotees

taking holy bath during festival of Ganga Dashara at Har-ki-Pauri, Haridwar

Hindus consider the waters of the Ganges to be both pure and

purifying Nothing reclaims order from disorder more than the waters of the

Ganges. Moving water, as in a river, is considered purifying in Hindu

culture because it is thought to both absorb impurities and take them away.The

swiftly moving Ganges, especially in its upper reaches, where a bather has to

grasp an anchored chain in order to not be carried away, is considered

especially purifying. What the Ganges removes, however, is not necessarily

physical dirt, but symbolic dirt; it wipes away the sins of the bather, not

just of the present, but of a lifetime.

A popular paean to the Ganges is the Ganga Lahiri composed

by a seventeenth century poet Jagannatha who, legend has it, was turned out of

his Hindu Brahmin caste for carrying on an affair with a

Muslim woman. Having attempted futilely to be rehabilitated within the Hindu

fold, the poet finally appeals to Ganga, the hope of the hopeless, and the

comforter of last resort. Along with his beloved, Jagannatha sits at the top of

the flight of steps leading to the water at the famous Panchganga Ghat in

Varanasi. As he recites each verse of the poem, the water of the Ganges rises

up one step, until in the end it envelops the lovers and carry them

away. "I come to you as a child to his mother," begins the Ganga

Lahiri.

I come as an orphan to you, moist with love.

I come without refuge to you, giver of sacred rest.

I come a fallen man to you, uplifter of all.

I come undone by disease to you, the perfect physician.

I come, my heart dry with thirst, to you, ocean of sweet wine.

Do with me whatever you will.

I come without refuge to you, giver of sacred rest.

I come a fallen man to you, uplifter of all.

I come undone by disease to you, the perfect physician.

I come, my heart dry with thirst, to you, ocean of sweet wine.

Do with me whatever you will.

Consort,

Shakti, and Mother

Ganga is a consort to all three major male deities of Hinduism. As Brahma's

partner she always travels with him in the form of water in his kamandalu (water-pot). She is

also Vishnu's

consort. Not only does she emanate from his foot as Vishnupadi in

the avatarana story, but is also, with Sarasvati and Lakshmi, one of

his co-wives.In one popular story, envious of being outdone by each other, the

co-wives begin to quarrel. While Lakshmi attempts to mediate the quarrel, Ganga

and Sarasvati, heap misfortune on each other. They curse each other to become

rivers, and to carry within them, by washing, the sins of their human

worshippers. Soon their husband, Vishnu, arrives and decides to calm the

situation by separating the goddesses. He orders Sarasvati to become the wife

of Brahma, Ganga to become the wife of Shiva, and Lakshmi, as the blameless

conciliator, to remain as his own wife. Ganga and Sarasvati, however, are so

distraught at this dispensation, and wail so loudly, that Vishnu is forced to

take back his words. Consequently, in their lives as rivers they are still

thought to be with him.

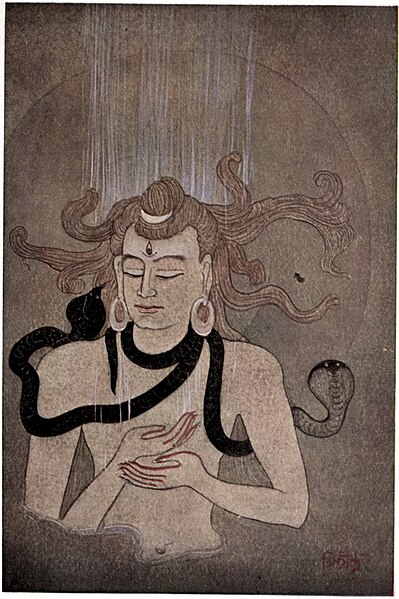

Shiva, as Gangadhara,

bearing the Descent of the Ganges, as the

goddess Parvati, the sage Bhagiratha, and the bull Nandi look

on (circa 1740).

It is Shiva's relationship with Ganga, that is the best-known in Ganges

mythology. Her descent, the avatarana is not a one time event,

but a continuously occurring one in which she is forever falling from heaven

into his locks and being forever tamed. Shiva, is depicted in Hindu iconography

as Gangadhara, the "Bearer of the Ganga," with Ganga,

shown as spout of water, rising from his hair.[71] The

Shiva-Ganga relationship is both perpetual and intimate. Shiva is

sometimes called Uma-Ganga-Patiswara ("Husband and Lord

of Uma (Parvati) and Ganga"), and Ganga often arouses the jealousy of

Shiva's better-known consort Parvati.

Ganga is the shakti or the moving, restless,

rolling energy in the form of which the otherwise recluse and unapproachable

Shiva appears on earth. As water, this moving energy can be felt, tasted, and

absorbed. The war-god Skanda addresses

the sage Agastya in the Kashi Khand of

the Skanda Purana in

these words:

One should not be amazed ... that this Ganges is really Power,

for is she not the Supreme Shakti of the Eternal Shiva, taken in the form of

water?

This Ganges, filled with the sweet wine of compassion, was sent out for the salvation of the world by Shiva, the Lord of the Lords.

Good people should not think this Triple-Pathed River to be like the thousand other earthly rivers, filled with water.

This Ganges, filled with the sweet wine of compassion, was sent out for the salvation of the world by Shiva, the Lord of the Lords.

Good people should not think this Triple-Pathed River to be like the thousand other earthly rivers, filled with water.

The Ganges is also the mother, the Ganga Mata (mata="mother")

of Hindu worship and culture, accepting all and forgiving all. Unlike

other goddesses, she has no destructive or fearsome aspect, destructive though

she might be as a river in nature. She is also a mother to other

gods. She accepts Shiva's incandescent seed from the fire-god Agni, which

is too hot for this world, and cools it in her waters. This union produces

Skanda, or Kartikeya, the god of war.In the Mahabharata, she is

the wife of Shantanu, and the mother of heroic

warrior-patriarch, Bhishma. When Bhishma is

mortally wounded in battle, Ganga comes out of the water in human form and

weeps uncontrollably over his body.

The Ganges is the distilled lifeblood of the Hindu tradition, of

its divinities, holy books, and enlightenment. As such, her worship does

not require the usual rites of invocation (avahana) at the beginning and

dismissal (visarjana) at the end, required in the worship of other gods.

Her divinity is immediate and everlasting.

Ganges in

classical Indian iconography

|

Early in ancient Indian culture, the river Ganges was associated

with fecundity, its redeeming waters and its rich silt providing sustenance to

all who lived along its banks. A counterpoise to the dazzling heat of the

Indian summer, the Ganges came to be imbued with magical qualities and to be

revered in anthropomorphic form. By the 5th century CE, an elaborate

mythology surrounded the Ganges, now a goddess in her own right, and a symbol

for all rivers of India. Hindu temples all over India had statues and

reliefs of the goddess carved at their entrances, symbolically washing the sins

of arriving worshippers and guarding the gods within. As protector of

the sanctum sanctorum, the goddess soon came to

depicted with several characteristic accessories: the makara (a

crocodile-like undersea monster, often shown with an elephant-like trunk),

the kumbha (an overfull vase), various

overhead parasol-like coverings, and a gradually increasing retinue of humans.

Central to the goddess's visual identification is the makara,

which is also her vahana, or mount. An

ancient symbol in India, it pre-dates all appearances of the goddess Ganga in

art. The makara has a dual symbolism. On the one hand, it

represents the life-affirming waters and plants of its environment; on the

other, it represents fear, both fear of the unknown it elicits by lurking in

those waters and real fear it instils by appearing in sight. The earliest

extant unambiguous pairing of the makara with Ganga is

at Udayagiri Caves in

Central India (circa 400 CE). Here, in Cave V, flanking the main figure of Vishnu shown in his boar

incarnation, two river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna appear

atop their respective mounts, makara and kurma (a

turtle or tortoise).

The makara is often accompanied by a gana,

a small boy or child, near its mouth, as, for example, shown in the Gupta

period relief from Besnagar, Central India,

in the left-most frame above. The gana represents both

posterity and development (udbhava). The pairing of the fearsome,

life-destroying makara with the youthful, life-affirming gana speaks

to two aspects of the Ganges herself. Although she has provided sustenance to

millions, she has also brought hardship, injury, and death by causing major

floods along her banks. The goddess Ganga is also accompanied by a dwarf

attendant, who carries a cosmetic bag, and on whom she sometimes leans, as if

for support. (See, for example, frames 1, 2, and 4 above.)

The purna kumbha or full pot of water is the

second most discernible element of the Ganga iconography. Appearing first

also in the relief in Udayagiri Caves (5th century), it gradually appeared more

frequently as the theme of the goddess matured. By the seventh century it

had become an established feature, as seen, for example, the Dashavatara temple, Deogarh, Uttar Pradesh (seventh century),

the Trimurti temple, Badoli, Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, and at the Lakshmaneshwar

temple, Kharod, Bilaspur,

Chhattisgarh, (ninth or tenth century), and seen very clearly

in frame 3 above and less clearly in the remaining frames. Worshipped even

today, the full pot is emblematic of the formless Brahman, as well

as of woman, of the womb, and of birth. Furthermore, the river goddesses

Ganga and Saraswati were both born from Brahma's pot, containing the celestial

waters.

In her earliest depictions at temple entrances, the goddess

Ganga appeared standing beneath the overhanging branch of a tree, as seen as

well in the Udayagiri caves. However, soon the tree cover had evolved into

a chatra or parasol held by an

attendant, for example, in the seventh-century Dasavatara temple at Deogarh. (The

parasol can be clearly seen in frame 3 above; its stem can be seen in frame 4,

but the rest has broken off.) The cover undergoes another transformation in the

temple at Kharod, Bilaspur (ninth or tenth century), where the parasol is

lotus-shaped, and yet another at the Trimurti temple at Badoli where the

parasol has been replaced entirely by a lotus.

As the iconography evolved, sculptors in the central India

especially were producing animated scenes of the goddess, replete with an

entourage and suggestive of a queen en route to a river to bathe. A relief

similar to the depiction in frame 4 above, is described in Pal 1997,

p. 43 as follows:

A typical relief of about the ninth century that once stood at

the entrance of a temple, the river goddess Ganga is shown as a voluptuously

endowed lady with a retinue. Following the iconographic prescription, she

stands gracefully on her composite makara mount and holds a

water pot. The dwarf attendant carries her cosmetic bag, and a ... female holds

the stem of a giant lotus leaf that serves as her mistress's parasol. The

fourth figure is a male guardian. Often in such reliefs the makara's

tail is extended with great flourish into a scrolling design symbolizing both

vegetation and water.

Kumbh Mela

A

procession of Akharasmarching over a makeshift bridge over

the Ganges River. Kumbh Mela at Allahabad, 2001.

Main

article: Kumbh Mela

Kumbh Mela is a mass Hindu pilgrimage in

which Hindus gather at the Ganges River. The normal Kumbh Mela is

celebrated every 3 years, the Ardh (half) Kumbh is celebrated

every six years at Haridwar and Prayag, the Purna (complete)

Kumbh takes place every twelve years at four places (Prayag (Allahabad), Haridwar, Ujjain,

and Nashik).

The Maha (great) Kumbh Mela which comes after 12 'Purna Kumbh

Melas', or 144 years, is held at Prayag (Allahabad).

The major event of the festival is ritual bathing at the banks of the river.

Other activities include religious discussions, devotional singing, mass

feeding of holy men and women and the poor, and religious assemblies where

doctrines are debated and standardized. Kumbh Mela is the most sacred of all

the pilgrimages. Thousands of holy men and women attend, and the

auspiciousness of the festival is in part attributable to this. The sadhus are

seen clad in saffron sheets with ashes and powder dabbed on their skin per the

requirements of ancient traditions. Some, called naga sanyasis,

may not wear any clothes.

Irrigation

The Ganges and its all tributaries, especially the Yamuna, have

been used for irrigation since ancient times. Dams and canals were common

in gangetic plain by fourth century BCE. The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin

has a huge hydroelectric potential, on the order of

200,000 to 250,000 megawatts, nearly half of which could be easily harnessed.

As of 1999, India tapped about 12% of the hydroelectric potential of the Ganges

and just 1% of the vast potential of the Brahmaputra.

Canals

Megasthenes, a Greek ethnographer who visited India

during third century BCE when Mauryans ruled India described the existence of

canals in the gangetic plain. Kautilya (also known as Chanakya), an advisor to Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of Maurya Empire, included the destruction of

dams and levees as a strategy during war. Firuz Shah Tughlaq had

many canals built, the longest of which, 240 km (150 mi), was built

in 1356 on the Yamuna River. Now known as the Western Yamuna Canal, it has

fallen into disrepair and been restored several times. The Mughal

emperor Shah Jahan built an irrigation canal on the Yamuna

River in the early 17th century. It fell into disuse until 1830, when it was

reopened as the Eastern Yamuna Canal, under British control. The reopened canal

became a model for the Upper Ganges Canal and all following canal projects.

The Ganges

Canal highlighted in red stretching between its headworks off the Ganges River

in Hardwar and

its confluences with the Jumna

River in Etawah and with the

Ganges in Cawnpore (now Kanpur).

The first British canal in India—with no Indian antecedents—was

the Ganges Canal built between 1842 and

1854. Contemplated first by Col. John Russell Colvin in 1836, it did not at

first elicit much enthusiasm from its eventual architect Sir Proby Thomas Cautley,

who balked at idea of cutting a canal through extensive low-lying land in order

to reach the drier upland destination. However, after the Agra famine of 1837–38, during which the East India Company's administration spent Rs. 2,300,000

on famine relief, the idea of a canal became more attractive to the Company's

budget-conscious Court of Directors. In 1839, the Governor General of India, Lord Auckland, with

the Court's assent, granted funds to Cautley for a full survey of the swath of

land that underlay and fringed the projected course of the canal. The Court of

Directors, moreover, considerably enlarged the scope of the projected canal,

which, in consequence of the severity and geographical extent of the famine,

they now deemed to be the entire Doab region.

The enthusiasm, however, proved to be short lived. Auckland's

successor as Governor General, Lord Ellenborough,

appeared less receptive to large-scale public works, and for the duration of

his tenure, withheld major funds for the project. Only in 1844, when a new

Governor-General, Lord Hardinge, was

appointed, did official enthusiasm and funds return to the Ganges canal

project. Although the intervening impasse had seemingly affected Cautley's

health and required him to return to Britain in 1845 for recuperation, his

European sojourn gave him an opportunity to study contemporary hydraulic works

in the United Kingdom and Italy. By the time of his return to India even more

supportive men were at the helm, both in the North-Western Provinces, with James Thomason as

Lt. Governor, and in British

India with Lord Dalhousie as

Governor-General. Canal construction, under Cautley's supervision, now went

into full swing. A 560 km (350 mi) long canal, with another

480 km (300 mi) of branch lines, eventually stretched between the

headworks in Hardwar, splitting into two branches below Aligarh, and its

two confluences with the Yamuna (Jumna in map) mainstem in Etawah and the Ganges in Kanpur (Cawnpore

in map). The Ganges Canal, which required a total capital outlay of £2.15

million, was officially opened in 1854 by Lord Dalhousie. According to

historian Ian Stone:

It was the largest canal ever attempted in the world, five times

greater in its length than all the main irrigation lines of Lombardy and

Egypt put together, and longer by a third than even the largest USA navigation

canal, the Pennsylvania Canal.

Dams and

barrages

A major barrage at Farakka was opened on 21 April

1975, It is located close to the point where the main flow of the river

enters Bangladesh, and the tributary Hooghly (also known as Bhagirathi)

continues in West Bengal past Kolkata. This barrage, which feeds the Hooghly

branch of the river by a 42 km (26 mi) long feeder canal, and its

water flow management has been a long-lingering source of dispute with

Bangladesh. Indo-Bangladesh Ganges Water

Treaty signed in December 1996 addressed some of the water

sharing issues between India and Bangladesh.

Tehri Dam was constructed on Bhagirathi River,

tributary of the Ganges. It is located 1.5 km downstream of Ganesh Prayag,

the place where Bhilangana meets Bhagirathi. Bhagirathi is called Ganges after

Devprayag. Construction of the dam in an earthquake prone area was

controversial.

Bansagar Dam was built on the Son River, a

tributary of the Ganges for both irrigation and hydroelectric power

generation.

Economy

A girl

selling plastic containers for carrying Ganges water, Haridwar.

The Ganges

Basin with its fertile soil is instrumental to the agricultural

economies of India and Bangladesh. The Ganges and its tributaries provide a

perennial source of irrigation to a large area. Chief crops cultivated in the

area include rice, sugarcane, lentils, oil seeds,

potatoes, and wheat. Along the banks of the river, the presence of swamps and

lakes provide a rich growing area for crops such as legumes, chillies, mustard,

sesame, sugarcane, and jute. There are also many fishing opportunities along

the river, though it remains highly polluted. Also the major industrial towns

of Unnao, Kanpur,

situated on the banks of the river with the predominance of tanning industries

add to the pollution.

Tourism

Tourism is another related activity. Three towns holy to Hinduism—Haridwar, Prayag (Allahabad), and Varanasi—attract

thousands of pilgrims to its waters to take a dip in the Ganges, which is

believed to cleanse oneself of sins and help attain salvation. The rapids of

the Ganges also are popular for river

rafting, attracting adventure seekers in the summer months. Also,

several cities such as Kanpur, Kolkata and Patna have developed riverfront

walkways along the banks to attract tourists.

Ecology and environment

Ganges

from Space

Human development, mostly agriculture, has replaced nearly all

of the original natural vegetation of the Ganges basin. More than 95% of the

upper Gangetic Plain has been degraded or converted to agriculture or urban

areas. Only one large block of relatively intact habitat remains, running along

the Himalayan foothills and including Rajaji National Park, Jim Corbett National Park,

and Dudhwa National Park.

As recently as the 16th and 17th centuries the upper Gangetic Plain harboured

impressive populations of wild Asian

elephants (Elephas maximus), Bengal

tigers (Panthera t. tigris), Indian

rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), gaurs (Bos

gaurus), barasinghas (Rucervus

duvaucelii), sloth bears(Melursus ursinus) and Indian

lions (Panthera leo persica).] In

the 21st century there are few large wild animals, mostly deer, wild

boars, wildcats, and small numbers of Indian

wolves, golden

jackals, and red and Bengal

foxes. Bengal tigers survive only in the Sundarbans area

of the Ganges Delta. The Sundarbands freshwater swamp ecoregion, however, is

nearly extinct. Threatened mammals in the upper Gangetic Plain

include the tiger, elephant, sloth bear, and four-horned antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis).

Lesser

florican (Sypheotides indicus)

Many types of birds are found throughout the basin, such

as myna, Psittacula parakeets, crows, kites, partridges,

and fowls. Ducks and snipesmigrate

across the Himalayas during the winter, attracted in large numbers to wetland

areas. There are no endemic birds

in the upper Gangetic Plain. The great Indian bustard (Ardeotis nigriceps)

and lesser florican (Sypheotides indicus)

are considered globally threatened.

The natural forest of the upper Gangetic Plain has been so

thoroughly eliminated it is difficult to assign a natural vegetation type with

certainty. There are a few small patches of forest left, and they suggest that

much of the upper plains may have supported a tropical

moist deciduous forest with sal (Shorea robusta) as a climax

species.

A similar situation is found in the lower Gangetic Plain, which

includes the lower Brahmaputra River. The lower plains contain more open

forests, which tend to be dominated by Bombax ceiba in association

with Albizzia

procera, Duabanga grandiflora,

and Sterculia

vilosa. There are early seral forest

communities that would eventually become dominated by the climax species sal (Shorea

robusta), if forest succession was allowed to proceed. In most places

forests fail to reach climax conditions due to human causes. The forests

of the lower Gangetic Plain, despite thousands of years of human settlement,

remained largely intact until the early 20th century. Today only about 3% of

the ecoregion is under natural forest and only one large block, south of

Varanasi, remains. There are over forty protected areas in the ecoregion, but

over half of these are less than 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi). The

fauna of the lower Gangetic Plain is similar to the upper plains, with the

addition of a number of other species such as the smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata)

and the large Indian civet (Viverra zibetha).

Fish

The catla (Catla

catla) is one of the Indian carp species that support major fisheries in

the Ganges

It has been estimated that about 350 fish species live in the

entire Ganges drainage, including several endemics.] In

a major 2007–2009 study of fish in the Ganges basin (including the river itself

and its tributaries, but excluding the Brahmaputra and Meghna basins), a total

of 143 fish species were recorded, including 10 non-native introduced species. The most diverse orders

are Cypriniformes (barbs

and allies), Siluriformes (catfish)

and Perciformes (perciform fish), each

comprising about 50%, 23% and 14% of the total fish species in the drainage.

There are distinct differences between the different sections of

the river basin, but Cyprinidae is the

most diverse throughout. In the upper section (roughly equalling the basin

parts in Uttarakhand) more than 50 species have been recorded and Cyprinidae

alone accounts for almost 80% those, followed by Balitoridae (about 15.6%) and Sisoridae (about 12.2%).Sections of the

Ganges basin at altitudes above 2,400–3,000 m (7,900–9,800 ft) above

sea level are generally without fish. Typical genera approaching this altitude

are Schizothorax, Tor, Barilius, Nemacheilus and Glyptothorax. About 100 species have been

recorded from the middle section of the basin (roughly equalling the sections

in Uttar Pradesh and parts of Bihar) and more than 55% of these are in family

Cyprinidae, followed by Schilbeidae (about

10.6%) and Clupeidae (about

8.6%). The lower section (roughly equalling the basin in parts of Bihar

and West Bengal) includes major floodplains and is home to almost 100 species.

About 46% of these are in the family Cyprinidae, followed by Schilbeidae (about

11.4%) and Bagridae (about 9%).

The Ganges basin supports major fisheries, but these have

declined in recent decades. In the Allahabad region

in the middle section of the basin, catches of carp fell from 424.91 metric

tons in 1961–1968 to 38.58 metric tons in 2001–2006, and catches of catfish

fell from 201.35 metric tons in 1961–1968 to 40.56 metric tons in

2001–2006. In the Patnaregion in the lower

section of the basin, catches of carp fell from 383.2 metric tons to 118, and

catfish from 373.8 metric tons to 194.48. Some of the fish commonly caught

in fisheries include catla (Catla catla), golden

mahseer (Tor putitora), tor

mahseer (Tor tor), rohu (Labeo

rohita), walking catfish (Clarias batrachus), pangas catfish (Pangasius pangasius), goonch catfish (Bagarius), snakeheads (Channa), bronze featherback (Notopterus notopterus)

and milkfish (Chanos chanos).

The Ganges basin is home to about 30 fish species that are

listed as threatened with the primary issues being overfishing (sometimes

illegal), pollution, water abstraction, siltationand invasive

species. Among the threatened species is the critically endangered Ganges

shark (Glyphis gangeticus). Several fish species migrate between

different sections of the river, but these movements may be prevented by the

building of dams.

Crocodilians

and turtles

The

threatened gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) is a large fish-eating crocodilian that

is harmless to humans[112]

The main sections of the Ganges River are home to the gharial (Gavialis

gangeticus) and mugger

crocodile (Crocodylus palustris), and the delta is

home to the saltwater crocodile (C. porosus). Among

the numerous aquatic and semi-aquatic turtles in the Ganges basin are the northern river terrapin (Batagur baska; only

in the lowermost section of the basin), three-striped roofed turtle (B.

dhongoka), red-crowned roofed turtle (B.

kachuga), black

pond turtle (Geoclemys hamiltonii), Brahminy river turtle (Hardella

thurjii), Indian black turtle (Melanochelys trijuga), Indian eyed turtle (Morenia petersi), brown roofed turtle (Pangshura smithii), Indian roofed turtle (Pangshura tecta), Indian tent turtle(Pangshura tentoria), Indian flapshell turtle (Lissemys punctata), Indian narrow-headed softshell

turtle (Chitra indica), Indian softshell turtle(Nilssonia gangetica), Indian peacock softshell turtle (N.

hurum) and Cantor's giant softshell turtle (Pelochelys

cantorii; only in the lowermost section of Ganges basin). Most of

these are seriously threatened.

Ganges

river dolphin

The

Gangetic dolphin in a sketch by Whymper and P. Smit, 1894.

The river's most famed fauna is the freshwater dolphin Platanista

gangetica gangetica, the Ganges river dolphin, recently declared India's national aquatic animal.[

This dolphin used to exist in large schools near to urban

centres in both the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, but is now seriously

threatened by pollution and dam construction. Their numbers have now dwindled

to a quarter of their numbers of fifteen years before, and they have become

extinct in the Ganges' main tributaries. A recent survey by the World Wildlife Fund found only 3,000 left in

the water catchment of both river systems.[

The Ganges river dolphin is one of only five true freshwater dolphins in the world. The other

four are the baiji (Lipotes vexillifer) of

the Yangtze River in China, now likely

extinct; the Indus river dolphin of the Indus River in

Pakistan; the Amazon river dolphin of the Amazon River in

South America; and the Araguaian river

dolphin (not considered a separate species until 2014) of

the Araguaia–Tocantins basin in Brazil. There are

several marine dolphins whose ranges include some freshwater habitats, but

these five are the only dolphins who live only in freshwater rivers and lakes.

Effects of

climate change

The Tibetan

Plateau contains the world's third-largest store of ice. Qin Dahe,

the former head of the China Meteorological Administration, said that the

recent fast pace of melting and warmer temperatures will be good for

agriculture and tourism in the short term; but issued a strong warning:

Temperatures are rising four times faster than elsewhere in

China, and the Tibetan glaciers are retreating at a higher speed than in any

other part of the world.... In the short term, this will cause lakes to expand

and bring floods and mudflows... In the long run, the glaciers are vital

lifelines for Asian rivers, including the Indus and the Ganges. Once they

vanish, water supplies in those regions will be in peril.

In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change (IPCC), in its Fourth Report, stated that the Himalayan

glaciers which feed the river, were at risk of melting by 2035. The IPCC has

now withdrawn that prediction, as the original source admitted that it was

speculative and the cited source was not a peer reviewed finding. In its

statement, the IPCC stands by its general findings relating to the Himalayan

glaciers being at risk from global warming (with consequent risks to water flow

into the Gangetic basin).

Pollution and environmental

concerns

Pollution of the Ganges

People

bathing and washing clothes in the Ganges in Varanasi.

The Ganges suffers from extreme pollution levels, caused by the

400 million people who live close to the river. Sewage from many cities

along the river's course, industrial waste and religious offerings wrapped in

non-degradable plastics add large amounts of pollutants to the river as it

flows through densely populated areas. The problem is exacerbated by the

fact that many poorer people rely on the river on a daily basis for bathing,

washing, and cooking. The World

Bank estimates that the health costs of water pollution in India equal

three percent of India's GDP. It has also been suggested that eighty

percent of all illnesses in India and one-third of deaths can be attributed to

water-borne diseases.

Varanasi, a city of one million people that many

pilgrims visit to take a "holy dip" in the Ganges, releases around

200 million litres of untreated human sewage into the river each day, leading

to large concentrations of faecal coliform bacteria. According

to official standards, water safe for bathing should not contain more than 500

faecal coliforms per 100ml, yet upstream of Varanasi's

ghats the river water already contains 120 times as much, 60,000

faecal coliform bacteria per 100 ml.

After the cremation of

the deceased at Varanasi's ghats the bones and ashes are thrown into the

Ganges. However, in the past thousands of uncremated bodies were thrown into

the Ganges during cholera epidemics, spreading the disease. Even

today, holy men, pregnant women, people with leprosy/chicken

pox, people who had been bitten by snakes, people who had committed

suicide, the poor, and children under 5 are not cremated at the ghats but are

floated free to decompose in the waters. In addition, those who cannot afford

the large amount of wood needed to incinerate the entire body, leave behind a

lot of half burned body parts.

After passing through Varanasi, and receiving 32 streams of raw

sewage from the city, the concentration of fecal coliforms in the river's

waters rises from 60,000 to 1.5 million, with observed peak values of 100

million per 100 ml. Drinking and bathing in its waters therefore carries a high

risk of infection.

Between 1985 and 2000, Rs. 10 billion,

around US$226 million, or less than 4 cents per person per year, were

spent on the Ganga

Action Plan, an environmental initiative that was "the largest

single attempt to clean up a polluted river anywhere in the

world." The Ganga Action Plan has been described variously as a

"failure", a "major failure".

According to one study,

The Ganga Action Plan, which was taken on priority and with much

enthusiasm, was delayed for two years. The expenditure was almost doubled. But

the result was not very appreciable. Much expenditure was done over the

political propaganda. The concerning governments and the related agencies were

not very prompt to make it a success. The public of the areas was not taken

into consideration. The releasing of urban and industrial wastes in the river

was not controlled fully. The flowing of dirty water through drains and sewers

were not adequately diverted. The continuing customs of burning dead bodies,

throwing carcasses, washing of dirty clothes by washermen, and immersion of

idols and cattle wallowing were not checked. Very little provision of public

latrines was made and the open defecation of lakhs of people continued along

the riverside. All these made the Action Plan a failure.

The failure of the Ganga Action Plan, has also been variously

attributed to "environmental planning without proper understanding of the

human–environment interactions,” Indian "traditions and

beliefs,"corruption and a lack of technical knowledge" and

"lack of support from religious authorities."

In December 2009 the World Bank agreed to loan India US$1

billion over the next five years to help save the river. According to 2010

Planning Commission estimates, an investment of almost Rs. 70 billion (Rs.

70 billion, approximately US$1.5 billion) is needed to clean up the river.

In November 2008, the Ganges, alone among India's rivers, was

declared a "National River", facilitating the formation of a National Ganga River Basin

Authority that would have greater powers to plan, implement and monitor

measures aimed at protecting the river.

In July 2014, the Government of India announced an integrated

Ganges-development project titled Namami Ganga and

allocated ₹2,037 crore for this purpose.

In March 2017 the High Court of Uttarakhand declared the Ganges

River a legal "person", in a move that according to one

newspaper, "could help in efforts to clean the pollution-choked

rivers." As of 6 April 2017, the ruling has been commented on in

Indian newspapers to be hard to enforce, that experts do not anticipate

immediate benefits, that the ruling is "hardly game changing," that

experts believe "any follow-up action is unlikely,"] and

that the "judgment is deficient to the extent it acted without hearing

others (in states outside Uttarakhand) who have stakes in the matter."

The incidence of water-borne and enteric diseases—such

as gastrointestinal disease, cholera, dysentery, hepatitis

A and typhoid—among

people who use the river's waters for bathing, washing dishes and brushing

teeth is high, at an estimated 66% per year.

Recent studies by Indian Council of Medical

Research (ICMR) say that the river is so full of killer pollutants

that those living along its banks in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Bengal are more

prone to cancer than anywhere else in the country. Conducted by the National Cancer

Registry Programme under the ICMR, the study throws up shocking findings

indicating that the river is thick with heavy metals and lethal chemicals that

cause cancer. According to Deputy Director General of NCRP A. Nandkumar, the

incidence of cancer was highest in the country in areas drained by the Ganges

and stated that the problem would be studied deeply and with the findings

presented in a report to the health ministry.

Water

shortages

Along with ever-increasing pollution, water shortages are getting

noticeably worse. Some sections of the river are already completely dry. Around

Varanasi, the river once had an average depth of 60 metres (200 ft), but

in some places, it is now only 10 metres (33 ft).

To cope with its chronic water shortages, India employs electric

groundwater pumps, diesel-powered tankers, and coal-fed power plants. If the

country increasingly relies on these energy-intensive short-term fixes, the

whole planet's climate will bear the consequences. India is under enormous

pressure to develop its economic potential while also protecting its

environment—something few, if any, countries have accomplished. What India does

with its water will be a test of whether that combination is possible.

Meghna River

The Meghna River (Bengali: মেঘনা নদী) is one of the most important rivers in Bangladesh, one of the three that forms the Ganges Delta, the largest delta on earth, which fans out to the Bay of

Bengal. A part of the Surma-Meghna

River System, Meghna is formed inside Bangladesh in Kishoreganj District above

the town of Bhairab Bazar by

the joining of the Surma and

the Kushiyara, both

of which originate in the hilly regions of eastern India as the Barak River. The Meghna meets its major tributary, the Padma, in Chandpur District. Other major tributaries of the Meghna

include the Dhaleshwari,

the Gumti, and

the Feni. The Meghna empties into the Bay of Bengal in Bhola District via four principal mouths,

named Tetulia (Ilsha),

Shahbazpur, Hatia, and Bamni.

Boat in Meghna River

The Meghna is the widest river among those that flow completely

inside the boundaries of Bangladesh. At a point near Bhola, Meghna is 12 km wide. In its lower

reaches this river's path is almost perfectly straight.

Course

The Meghna is formed inside Bangladesh by

the joining of the Surma and Kushiyara rivers originating from the

hilly regions of eastern India. Down

to Chandpur, Meghna is hydrographically referred to as

the Upper Meghna. After the Padma joins,

it is referred to as the Lower Meghna.

Near Muladhuli in Barisal district,

the Safipur

River is an offshoot of the Surma that creates one of the main

rivers in South Bengal. 1.5 km wide, this river is one of the widest in

the country as well.

At Chatalpar of Brahmanbaria District,

the river Titas emerges from Meghna and after circling two large bends by

a distance of about 150 mile, falls into the Meghna again near Nabinagar Upazila. The Titas forms as a single

stream but braids into two distinct streams which remain separate before

re-joining the Meghna.

A view of

the Meghna from a bridge

In Daudkandi, (Comilla District), the Meghna is joined by

the Gumti River,

which increases the Meghna's waterflow considerably. The pair of bridges over

the Meghna and Gumti are two of the country's largest bridges.

Meghna is again reinforced by the Dhaleshwari before Chandpur. Further

down, the Padma River- the largest distributary of the Ganges in

Bangladesh, along with the Jamuna River-

the largest distributary of the Brahmaputra, join with the Meghna in Chandpur

District, resulting in the Lower Meghna.

When the brown and hazy water of the Padma mix with the clear

water of the Upper Meghna, the two streams do not mix but flow in parallel down

to the sea - making half of the river clear and the other half brown. This

peculiarity of the river is always a great attraction for people.

After Chandpur, the

combined flow of the Padma, Jamuna and

Meghna moves down to the Bay of

Bengal in an almost straight line, braiding occasionally into a

number of riverines including the Pagli, Katalia, Dhonagoda, Matlab and

Udhamodi. All of these rivers rejoin the Meghna at different points downstream.

Near Bhola, just

before flowing into the Bay of Bengal, the river again divides into

two main streams in the Ganges delta and separates an island from both sides of

the mainland. The western stream is called Ilsha while the eastern one is

called Bamni.

Jamuna River

(Bangladesh)

The Jamuna River (Bengali: যমুনা Jomuna)

is one of the three main rivers of Bangladesh. It is

the main distributary channel

of the Brahmaputra River as

it flows from India to

Bangladesh. The Jamuna flows south and joins the Padma River (Pôdda),

near Goalundo Ghat, before meeting the Meghna River near

Chandpur. It then flows into the Bay of Bengal as

the Meghna River. It is the National river of

Bangladesh.

The Brahmaputra-Jamuna is a classic example of a braided river and

is highly susceptible to channel migration and avulsion.[1] It is characterised by a

network of interlacing channels with numerous sandbars enclosed

between them. The sandbars, known in Bengali as chars,

do not occupy a permanent position. The river deposits them in one year, very

often to be destroyed later, and redeposits them in the next rainy season. The

process of bank and deposit erosion together with redeposition has been going

on continuously,[2] making it difficult to

precisely demarcate the boundary between the district of Pabna on one side and

the districts of Mymensingh Tangail and Dhaka on the other. The breaking of a char or

the emergence of a new one is also a cause of much violence and litigation. The

confluence of the Jamuna River and Padma River is unusually unstable and has

been shown to have migrated southeast by over fourteen kilometres between 1972

and 2014.

Course

In Bangladesh, the Brahmaputra is joined by the Teesta River (or Tista), one

of its largest tributaries. The Teesta earlier ran due south from Jalpaiguri in three channels, namely,

the Karatoya to

the east, the Punarbhaba in

the west and the Atrai in the

centre. The three channels possibly gave the name to the river as Trisrota "possessed

of three streams" which has been shortened and corrupted to Teesta. Of